BLOG

This is the final post of a series focusing on each of the four stages (or planes) of development: birth through age six, ages six to twelve, ages twelve to eighteen, and ages eighteen to twenty-four. Montessori pedagogy calls for a big picture perspective that incorporates the fundamental principles of human development at each stage of development and how we can best provide for a developing young person in each stage. A Path Toward Maturity and Contribution to Society The journey of human development, as envisioned by Dr. Maria Montessori, is marked by four distinct planes. Each plane represents a different phase in an individual's growth, and the fourth plane, spanning from 18 to 24 years of age, is no exception. This phase, which Montessori refers to as Maturity, signals the culmination of psychological and physical growth and paves the way for young adults to step into the world as a fully formed individuals capable of significant contributions to society. Characteristics of the Fourth Plane The fourth plane represents a time when individuals reach the height of their development and begin to assume their role in society. Unlike the earlier planes, the psychological changes during this period are less dramatic and more internal, and the focus shifts to understanding oneself and the world beyond one’s immediate needs. Whereas the body completes its physical maturation, the mind embarks on the task of understanding how it can contribute to humanity. In The Four Planes of Education, Dr. Montessori writes, “The individual should be the man who knows how to make his own choice of action having passed to perfection the preceding phases. He should be as a live spark and aware of the open gate to the potentialities of prospective human life and of his own possibilities and responsibilities” (p. 15). This encapsulates the essence of the fourth plane— young adults’ newfound ability to make independent choices while being aware of their potential impact on society. In this stage, individuals are not merely focused on themselves but are also learning to engage with the world beyond their personal ego. The question that arises is not “Who am I?” but “What can I do?” This shift from self-centeredness to a broader, more collective view of life signifies the maturity that defines the fourth plane. Conquest of Independence One of the key aspects of the fourth plane is the conquest of independence, particularly economic independence. This phase marks a time when individuals strive to become self-sufficient within the larger society. Young adults move beyond the dependency of childhood and adolescence, assuming more responsibility for their own life, finances, and future. This is a period when a personal mission begins to take shape. Young adults start to solidify their goals, whether academic, professional, or personal, and work toward them with a growing sense of purpose. Dr. Montessori believed that achieving economic independence was crucial, as it not only provides the means to live but also fosters a sense of autonomy and responsibility. Observable Examples of Development Physically, by the fourth plane, development is largely complete. The dramatic growth spurts of the previous stages have slowed, and young adults now have full mastery over their body. Health is typically stable, and there is an overall sense of well-being. Much like the second plane, the fourth plane is also conducive to intellectual pursuits, particularly those that lead to specialization in areas essential for a future career. This is when our young adults are honing skills that will serve them in the professional world, whether through higher education, apprenticeships, or other forms of specialized learning. The fourth plane is also a time when individuals, having developed a solid understanding of themselves, are ready to take on more significant intellectual and social responsibilities. This is when they truly start asking the big questions, such as, “How can I contribute to the world?” It is at this stage that young adults embark on the exploration of their "cosmic task," a concept Montessori introduced in the second plane, which refers to the idea that every individual has a unique role to play in the larger story of humanity. The Role of the Supportive Environment With significant internal growth happening during the fourth plane, the role of the external environment remains crucial. A supportive environment during the preceding planes can have a profound effect on how individuals move through this stage. If our young adults have been nurtured in an environment that promotes autonomy, responsibility, and respect for their capacity to make choices, they are more likely to enter adulthood with the skills and mindset necessary to thrive in society. To prepare for their careers during this time, many young adults pursue higher education, either through university studies or vocational training. Alternatively, they may enter the workforce, beginning to take on professional roles that contribute to society. This is also a time when many young adults leave the family home and start families of their own, further solidifying their place in the world as independent adults. Dr. Montessori, unfortunately, did not have the opportunity to explore this phase in depth. However, we can imagine a world where every individual has been given the best possible environment throughout the previous planes of development. In such a world, adults who emerge from the fourth plane are equipped not only with the knowledge and skills to succeed but also with a profound sense of responsibility toward the greater good. An Enlightened Society The ideal outcome of the fourth plane is individuals who not only seek personal success but also work toward the welfare of humankind. Young adults who have passed through the earlier planes of development with the support of nurturing environments can enter society with a strong social conscience, eager to contribute to the collective well-being of humanity. They see the interconnectedness of all people and seek ways to address societal issues and contribute to the common good. Imagine a world in which all young adults, having been guided through the previous developmental stages, emerge from the fourth plane ready to play their roles in society—not only as self-sufficient individuals but as enlightened members of a larger human community. This vision encapsulates the Montessori ideal: a world where everyone has the potential to contribute meaningfully to the advancement of humanity as a whole. The fourth plane of development is not merely a time for self-discovery but a time for self-realization and societal contribution. Young adults, secure in their independence, prepare to engage with the world in ways that transcend personal goals, focusing instead on broader responsibilities. By fostering an environment that nurtures growth and independence, we set the stage for a society composed of individuals capable of making meaningful contributions to humanity’s collective well-being. Curious to see how attention to the characteristics and needs of earlier stages of development can support an enlightened society? Schedule a tour today!

This post is the third installment in our series exploring four stages of human development from a Montessori perspective. The Montessori approach takes a holistic view of growth, recognizing the unique needs of young people at every stage—birth to age six, six to twelve, twelve to eighteen, and eighteen to twenty-four—and adapts learning environments to support natural development at each stage. By understanding these key phases, we can better nurture young individuals as they progress on their journey to maturity. Adolescence (Age Twelve to Eighteen) Adolescence is often seen as a turbulent stage in life, sometimes even labeled as dysfunctional or something to endure. However, Dr. Maria Montessori viewed this vital period of human development as a time in our lives that deserves respect and understanding. In Montessori education, adolescence is honored as a time of transition, a phase of development that, in many ways, mirrors the first six years of life. Just as the early years are marked by rapid transformation and the shaping of the individual, adolescence marks the transformation from childhood into adulthood. Adolescent Development The third plane of development, which typically begins at age twelve and continues through the teenage years, is one of significant physical, emotional, and social transformation. This period is characterized by the onset of puberty, hormonal changes, and dramatic physical shifts. Adolescents, much like children in the first plane of development, experience rapid change, but this time it is in preparation for adulthood and potential child-rearing. As a result, adolescents require more sleep and are more susceptible to health issues (e.g. acne, depression, and eating disorders). A key focus during this stage is the conquest of social and economic independence. Humans on the journey to adulthood need to function in social organizations, which requires intellectual and social skills. Adolescents also need to experience how economic interdependency works and they want to learn about different roles in economic systems. To do so, they need the awareness and skills to contribute in meaningful ways. Social engagement is how we function as humans. Economic contribution and interdependency is how we meet our needs. Adolescents are no longer passive observers of society; instead, they strive to become active participants and contributors. Like during the first plane, adolescents learn best through hands-on experiences that benefit society, which reinforces their desire to contribute in meaningful ways. Adolescents as Social Newborns Dr. Montessori often referred to early adolescence as the "newborn" stage of adulthood, highlighting the vulnerability and transformation that adolescents undergo. This period of rapid physical and emotional development mirrors the developmental intensity of the first years of life. Adolescents are not just growing in terms of physical stature but also in terms of emotional and social maturity. Much like a newborn, adolescents are learning how to navigate the complexities of the world around them. They are developing a sense of self and finding their place in society. The challenge of the third plane is to help them build this self-confidence and self-worth, while guiding them through the emotional turbulence that often accompanies this stage. Holistic Development: Physical, Emotional, and Social Growth Montessori's approach to adolescence is deeply holistic. We emphasize the importance of addressing the adolescent's physical, emotional, and social needs, recognizing that these areas are interconnected and cannot be separated in the developmental process. Physical Development Adolescents undergo significant physical changes during this time, including hormonal fluctuations and rapid growth. Brain development continues with an oversupply of gray matter and pruning of neural pathways, which influences behavior and learning capacity. Key physical needs include: Engaging in physical activity and hands-on work Maintaining a healthy diet Ensuring adequate sleep Emotional and Psychological Development Adolescents experience strong emotional swings and are highly self-conscious. They are forming their identities and are very aware of peer perceptions. Balancing these emotions and navigating their evolving sense of self can be challenging. Emotional needs include: Opportunities to build confidence and independence Safe yet challenging environments Support in self-expression and identity formation Social Development Social connections become increasingly important during adolescence. Adolescents seek peer approval and loyalty and often engage in risk-taking behaviors as they establish their place within their social circles. They learn best through collaboration and social interaction. Social needs include: Opportunities for collaboration with peers Mentorship from adults Meaningful and relevant social engagement Moral and Intellectual Development Dr. Montessori emphasized the adolescent’s sensitivity to issues of justice and personal dignity. This stage is a critical time for developing a strong sense of fairness and the desire to contribute meaningfully to society. As they mature, adolescents begin to understand the value of their contributions to the world around them. Though their intellectual development might seem secondary due to emotional upheavals, it remains essential. As their brains undergo significant rewiring and neural pruning, adolescents still benefit from intellectual opportunities and challenges, as well as strong moral foundations. The Role of Work and Contribution Just as it was in earlier planes of development, work remains a vital aspect of adolescence. Adolescents have a strong desire to contribute to society and have their efforts recognized. Through work and activity, adolescents bolster their self-esteem and gain a sense of accomplishment. The educational model proposed by Dr. Montessori focuses on land-based work and cooperative community living, which provide ways for adolescents to engage in meaningful activities. This model supports adolescents’ physical well-being, fosters social development, and prepares them for economic independence. Through hands-on work, adolescents not only contribute to their immediate communities but also develop a sense of responsibility and understanding of the value of work. Supporting Adolescents Through Their Development To meet the developmental needs of adolescents, we need to offer supportive environments. Dr. Montessori envisioned a community where adolescents could live and work together, gaining both physical and emotional nourishment. Providing opportunities for physical activity, collaboration, and self-expression helps adolescents develop into confident, capable adults. Adolescents need both freedom and guidance. While they push away from adults as they seek independence, they still require boundaries, structure, and mentorship. Adults play a critical role in supporting adolescents as they navigate this transformative stage. Understanding adolescence through the Montessori lens allows us to appreciate this period as one of profound transformation. By honoring the physical, emotional, social, and moral development of adolescents, we can provide them with the support they need to transition confidently into adulthood. With a holistic approach that integrates meaningful work, opportunities for self-expression, and guidance from adults, adolescents can be empowered to become the capable, interdependent adults society needs. Visit our school today to learn more!

Understanding human development at each stage is crucial to fostering optimal growth. This belief forms the foundation of Montessori education, which is deeply rooted in the developmental needs of children. This post is the second in a series that explores the four stages of human development: birth through age six, ages six to twelve, ages twelve to eighteen, and ages eighteen to twenty-four. Each of these stages, or planes of development, comes with unique needs and capacities, and understanding them allows us to better support children in their educational journey. Childhood (Age Six to Twelve) Unlike the dramatic changes seen in infancy and adolescence, the second plane of development (ages six to twelve) is often viewed as a period of relative stability. This phase serves as a critical time for children to build upon their early experiences while preparing for the transitions that will come in adolescence. Despite its importance, this period is sometimes overlooked in society, but it is essential for the development of social, intellectual, and emotional skills that will serve as a foundation for later life. Key Characteristics of Elementary Children At the core of this stage are several observable characteristics. Physical Sturdiness and Stability Children in this stage experience a steady period of physical growth. They lose their primary teeth and gain adult teeth. Their skin loses its baby softness. Their hair even gets coarser and darker. Their body becomes leaner and stronger, with the soft, rounded contours of early childhood giving way to a more defined physical form. Despite these changes, growth slows down compared to the rapid pace of the first plane. This time also brings greater stability in health and coordination. Reasoning and Abstraction While children in the first plane absorb information effortlessly and even unconsciously, the second plane is marked by a growing capacity for reason and abstraction. No longer content with simply absorbing facts, children seek to understand the underlying causes of things. They begin to ask “why” questions and develop the ability to think logically and critically about the world around them. Their imagination flourishes and they love being able to transcend time and space, mentally traveling through history or exploring possible futures. Conquest of Independence This is a time when children transition from sensorimotor learning to becoming intellectual explorers. The intellectual independence they gain during this phase fuels their studies of mathematics, history, geography, art, and music. Montessori classrooms provide opportunities for children to explore these subjects with the motto: “Don’t tell me. I’ll figure it out myself.” Their journey toward independence extends beyond the academic to include a growing capacity for social reasoning and moral judgment. The Herd Instinct and Socialization One of the defining features of children in the second plane is their social nature. Children at this age exhibit a strong "herd instinct"—the need to belong to a group and collaborate with peers. They begin forming micro-societies and creating their own rules, roles, and expectations. These experiences allow them to practice social interactions and develop their conscience. It’s worth noting that as adult-directed activities (e.g. afterschool sports and classes) increase, children have fewer opportunities to work out social dynamics independently. Moral Development and a Sense of Fairness As elementary-age children seek independence, they also begin to develop a sense of morality. Children at this stage are sensitive to fairness and justice, and are likely to voice concerns when they perceive inconsistencies. This is when we frequently hear, “It’s not fair!” This stage is about the exploration of right and wrong and the ability to question rules and authority. The drama that unfolds in the classroom is often part of this process, as children navigate the complexities of social rules and develop their moral code. A Fascination with the Extraordinary Second plane children are drawn to the extraordinary, whether in the form of superheroes, mythical creatures, or fascinating civilizations. Their imagination is sparked by the idea of powers beyond the ordinary, and they are eager to explore cultures and histories that seem larger than life. This fascination with the exceptional provides them an avenue for exploring concepts of heroism, strength, and the human condition. A Supportive, Community-Based Learning Environment In a Montessori classroom, children are encouraged to work both independently and in groups. As such, the prepared environment of the second plane is designed to foster collaboration while allowing space for individual exploration. Group activities allow children to develop their social skills, negotiate rules, and practice taking on different roles within a community. Through these experiences, they are able to form their own moral code and develop their identity in relation to the group. Children in this stage also have a thirst for knowledge that goes beyond what is available in the classroom. Montessori education encourages “Going Out” experiences—trips beyond the school to explore the wider world. These excursions allow children to engage with real-world problems, develop planning and execution skills, and build a deeper understanding of the subjects they are studying. Through these experiences, children come to see themselves as active participants in the world around them. Montessori referred to the educational experience in the second plane as "cosmic education." In this phase, children are introduced to the universe as a whole, with an emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life. The Montessori curriculum for this stage revolves around the Five Great Lessons, which invite children into discovering more about the universe, the formation of the earth, the coming of plants and animals, the arrival of humans, and the development of written language and numbers. From these lessons, all areas of study—botany, geography, history, zoology, language, and more—emerge, inspiring awe and gratitude for the universe and humankind’s place within it. Support from Home and Community While second plane children are eager to explore beyond the family and classroom, they still require the strong support of their home, school, and peer group. Social activities become increasingly important, as group work provides them with the opportunity to practice collaboration, moral judgment, and self-expression. A strong, supportive environment—both at home and at school—helps children navigate this important stage in their development. Curious to see how a school environment can meet the needs of six- to twelve-year-olds while inspiring deep learning? Schedule a tour of our classrooms!

Imagine education from a fresh perspective—one that sees children not as empty vessels waiting to be filled but as whole individuals embarking on a lifelong journey of self-formation. From the moment of birth, children are driven by powerful internal forces that guide their growth and help them adapt to their unique time, place, and culture. This remarkable ability to evolve and adapt is a defining trait of our human species. The Montessori approach to education is built upon this profound understanding of human development. Dr. Maria Montessori dedicated her life's work to observing how children grow and change over time, identifying key developmental stages that shape their path to maturity. Through her scientific observations, she identified four distinct planes of development, each with its own unique characteristics and needs. In this four-part blog series, we’ll explore each of these four stages—birth to age six, six to twelve, twelve to eighteen, and eighteen to twenty-four—unpacking how Montessori education adapts to support children’s evolving needs at every phase of growth. By understanding these developmental stages, we can better support young people on their journey to becoming capable, independent, and fulfilled individuals. Infancy (Birth to Age Six) The first plane of development is an extraordinary period of psychological and physical growth. Newborns enter the world entirely dependent, unable to move or communicate. Yet, within just six years, they are walking, talking, and asserting their independence with intellect and will. Characteristics of the First Six Years During this transformative stage, children require ample sleep to support their rapid development. However, when they are awake, their curiosity knows no bounds. They explore their surroundings with boundless energy, using their senses to touch, smell, taste, hear, and examine everything in their environment. Conquest of Independence One of the primary goals during this stage is achieving functional independence. Children are eager to take care of their own needs and are naturally inclined to observe and imitate the actions of adults. The mantra of children at this stage is: “Help me do it myself!” Sensitive Periods Children in the first plane experience sensitive periods—windows of opportunity when they are uniquely receptive to acquiring essential skills. Movement : Young children need movement to develop brain-body integration. Order : They crave order to make sense of their surroundings, learning what happens and how objects are used. Language Acquisition : This is a critical period for language development, during which children absorb words and speech patterns effortlessly. These sensitivities drive children’s development, shaping their understanding of the world. Observable Milestones One of the most profound achievements in this phase is the acquisition of spoken language. Talking to newborns, for example, stimulates vocal cord development, and astonishingly, their vocal cords vibrate when adults speak to them. From being essentially mute at birth, toddlers can have a vocabulary of around 200 words by age two and an impressive 10,000 words by the end of this phase. This makes it essential to provide a language-rich environment during these formative years. Physically, this period is one of monumental growth. Children progress from being immobile to sitting, crawling, walking, speaking, and independently eating. As adults, we must be mindful about supporting rather than hindering this development. We want to offer rather than limit growth opportunities for our children! The Sub-Planes: Ages 0 to 3 and Ages 3 to 6 The first plane of development can be divided into two distinct sub-phases: Ages 0 to 3 : Children’s development is largely unconscious, driven by innate forces. During this phase, children absorb the world around them and do so without any filters. It’s important during this time that adults respect children’s natural developmental path without imposing external motivations. Ages 3 to 6 : During these years, children become more consciously aware of their actions and motivations. This is when we see the emergence of children’s willpower and the powerful drive to classify and understand their environment. Children become more conscious learners. As they grow, children naturally identify patterns, similarities, and differences based on their experiences. They construct their understanding of the world from scratch, and active experiences in their environment play a crucial role in shaping their cognitive development. Social Development in the First Plane During their first three years, children form strong bonds with their primary caregivers and family, finding comfort in a small social circle. They prefer solitary exploration and engage in parallel play. By age three, children seek a broader social experience beyond the family. They require opportunities to interact with peers and engage in community life, which fosters independence and social development. Creating a Supportive Environment Providing the right environment is crucial to supporting children during their early years. Key elements of an optimal environment include: A Secure Home : A safe and loving home helps children build trust and confidence in the world around them. Freedom to Explore : Children need space and opportunities to move and explore safely, both indoors and outdoors. Language Exposure : A rich linguistic environment helps children build vocabulary and develop confidence in self-expression. Participation in Daily Life : Involvement in practical life activities helps children develop independence and a sense of belonging. Cultural Experiences : Exposure to family traditions, rituals, and cultural practices helps children adapt to their culture and understand their place within it. As children develop over the course of this stage of life, they also benefit from being part of a social community and, in the process, learn valuable lessons about cooperation, sharing, and responsibility. By understanding the characteristics and needs of the first plane of development, we can create environments that nurture children’s natural growth, independence, and exploration.

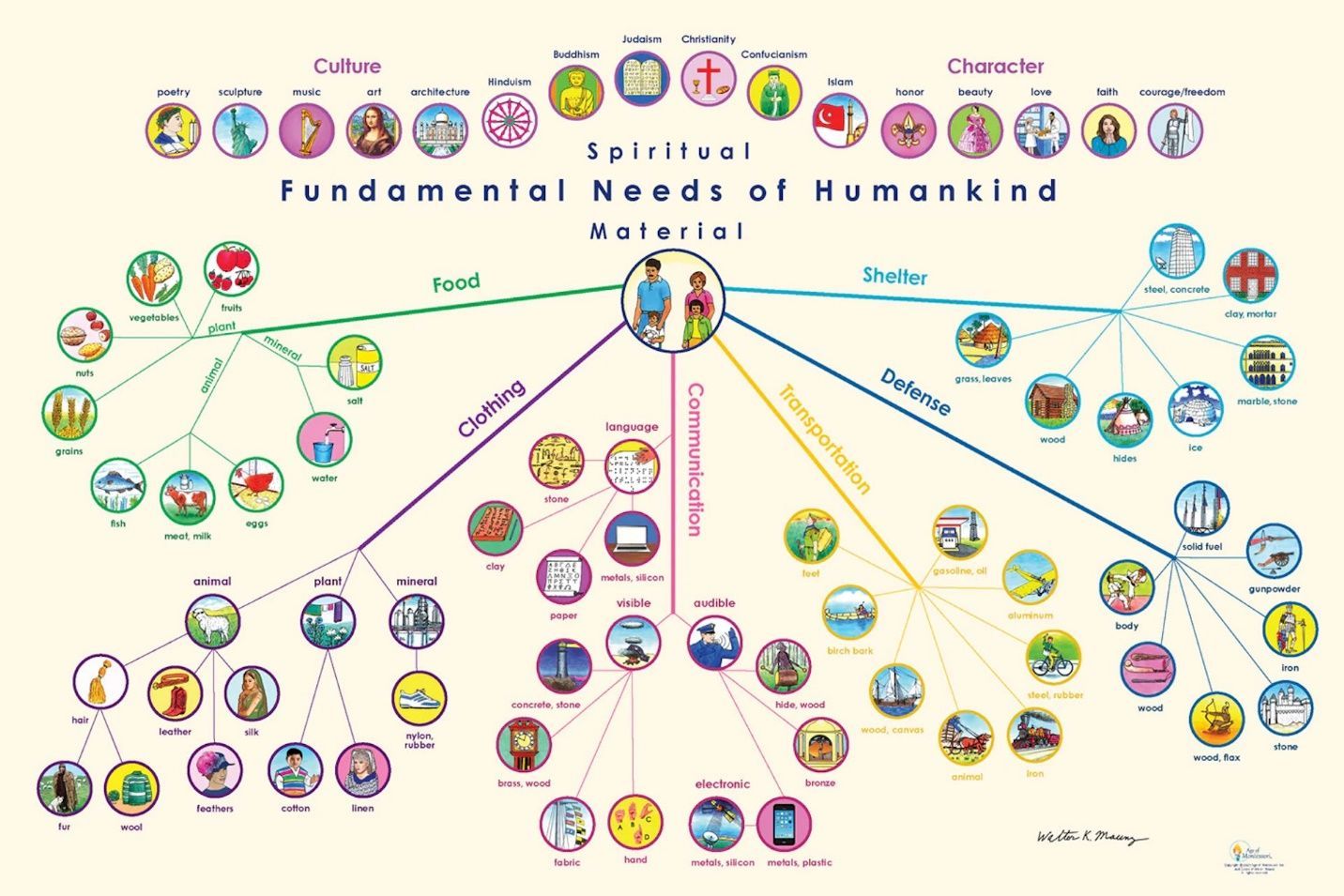

Exploring Human Connection: The Fundamental Needs Charts in Montessori In the Montessori elementary classroom, we support children’s natural curiosity about what it means to be human. One of the tools we use for this exploration is the Fundamental Needs Charts, which illustrate the universal needs that connect all people, past and present. Understanding Our Shared Humanity The purpose of these charts is to help children recognize their own needs and see how human beings across time and cultures have worked to fulfill them. Through this, children begin to develop a deeper awareness of their place in history and the common threads that unite all people. There are two charts that children use first as an overview and then as a tool for research. The first chart provides a broad overview of fundamental needs, divided into material needs (food, shelter, clothing, defense, transportation) and spiritual needs (art, music, religion, communication). The second chart focuses specifically on the human need for food, a concept that even the youngest elementary students can appreciate! Unlike traditional text-heavy resources, these charts rely on visual representations, which makes them accessible to younger elementary children. The charts also provide a visual model of how to organize an investigation into ancient civilizations and cultures. A Framework for Exploration Elementary-aged children are naturally curious about how things work and why people live the way they do. The Fundamental Needs Charts provide a structured way to study history and culture, allowing children to ask meaningful questions: How did different civilizations meet their needs for food and shelter? How did people create art, music, and systems of belief? What innovations, like the wheel, changed the way humans lived? Are spiritual needs as essential as physical ones for survival? These questions encourage children to think critically and compare cultures in a way that fosters both curiosity and respect for diversity. From Concrete to Abstract Thinking At first, children relate to physical needs like food and warmth because they have personally experienced hunger or cold. They also begin to grasp more abstract concepts, such as the role of art, music, and communication in human development. We introduce the first chart through conversation: What did you have for breakfast this morning? How did you get to school? Did you wear a seat belt? Why did you choose the clothes you have on today? What do you plan to do this weekend? We often write little slips with students’ answers. Then, we display the first chart and, together with the children, figure out how to put the different answers into the different categories. Children love this personal connection to the material, and the process lays the stage for how information can be organized thematically. Encouraging Independent Research The Fundamental Needs Charts do not present every possible human need–this is intentional. Instead, they provide a model that encourages children to create their own charts based on their research. This process deepens their understanding and allows them to make connections between cultures in a meaningful way. Younger children often love making “needs” collages from magazine pictures or even charts of their own personal “fundamental needs” such as “What I Eat.” Sometimes, children may make booklets or write a story or report about a particular aspect of the chart, such as “How We Get to School” or foods that come from fish or foods that are flowers! Or they may make a chart with all the different ways human beings transport themselves, or about human houses. The possibilities are endless! As they continue their studies, older children transition to The History Question Charts, which rely more on text and research. These allow for a more detailed examination of historical patterns, further reinforcing the idea that history is a story of human beings working to meet their needs. Education for Peace Dr. Maria Montessori believed that education should help children see themselves as part of a larger human family. By studying the universal needs that all people share, children develop a sense of human solidarity through space and time. They learn that while cultures may differ in their approaches, our fundamental needs unite us all. This understanding fosters empathy, respect, and a sense of interconnectedness—essential components of education for peace. The Fundamental Needs of Human Beings Charts are more than just learning tools; they are a gateway to understanding human history, culture, and identity. Visit our classrooms to see how our learning activities help young people become interconnected citizens!

In Montessori education, we emphasize community, not just as an abstract concept, but as a lived daily experience. From the very beginning of life, we emphasize carefully prepared environments that foster a deep sense of belonging and connection. What Is Community? The word community comes from the Latin communis, meaning “common, public, general, or shared by all or many.” In addition to shared space, in Montessori, we also think about community as a shared sense of meaning, values, and connection. At its core, community begins with the most fundamental human group: the family. Families form children’s first social experience and the first place where values, culture, and expectations are passed down. This bond has helped humans survive and thrive throughout history. Partnering with Families In the Montessori approach, we honor and respect each family's unique values, striving to foster strong home-school relationships. Our partnership with families is a mutual journey—one in which the adult caregivers at school and home come together with a shared purpose: to nurture children’s natural growth. Building the Toddler Community We design our learning environments—both indoors and outdoors—to meet each child where they are, providing just the right level of challenge, comfort, and beauty. In creating community, we focus on essential, concrete elements like people, space, and materials, while also attending to intangible aspects that provide a profound sense of order. The People : The adults—both the lead guide and trained assistants—focus on personal and professional preparation. Their role is not to direct the child but to support their natural development with presence, purpose, and peacefulness. The Space : The physical environment must be appropriately sized, thoughtfully arranged, and aesthetically pleasing. If it’s too large, children can feel lost or overstimulated. If it’s too small, they may feel crowded and unsettled. We design every detail—from the furniture to the flow of the day—with intention. The Materials : Everything in the classroom is purposeful, developmentally appropriate, and in harmony with Montessori principles. We carefully select materials to support children’s movement, independence, concentration, and sense of order. Profound Order : A true Montessori community also relies on an invisible but essential structure: the order that underlies everything. Children have a fundamental need for order, especially during the first six years of life when they are in their sensitive period for order. External order—seen in routines, consistent expectations, and a well-organized space—helps children form inner order, which is the foundation of emotional regulation, concentration, and autonomy. If children do not experience order in their lives, they must expend energy trying to create it—energy that should instead be used for self-construction. That is why order must exist not just in the physical environment, but also in the adults’ behavior and in the flow of the day. A sense of control, predictability, and respect enables toddlers to flourish as they begin to form their personalities. The Role of the Prepared Adult As we create and cultivate our learning communities, we also recognize the significance of our role as adults in creating a community where toddlers feel safe, supported, and free to grow. While we play a critical role in creating and maintaining a beautiful environment, we also recognize that it belongs to the children for their growth and development. To ensure that we support this development, we strive to master the art of observation, which enables us to identify what children need to aid their growth. With a deep understanding of the purpose of every material in the classroom, we can then connect children to meaningful work through intentional and respectful presentations. We also practice humility, recognizing that children are often more in tune with their needs than we are. Our work with toddlers requires us to respect each child’s human potential, even when behavior is challenging, and to love unconditionally, accepting children for who they are, not who we want them to be. This practice means that we regularly reflect on our own work, always striving to improve so that we can better serve the children. A Living, Breathing Community Creating a Montessori community for toddlers is both an art and a science that requires intentional environments, well-prepared adults, and a deep respect for children’s developmental journey. At its heart, the Montessori Toddler Community is a shared space where children learn how to be in the world—together. It is here they first experience what it means to belong, to contribute, and to grow with others. Schedule a visit to see what an intentionally designed community looks like in action!

At the heart of Montessori education is a deep respect for human potential. The core of Montessori philosophy and practice originated when Dr. Maria Montessori, as part of her medical school training, worked with children who had developmental delays. Dr. Montessori observed that the children needed something different, so she provided them with materials and an environment that truly supported their development. The result? The children demonstrated remarkable growth. This discovery has forever changed our understanding of learning and the human experience. A Scientific Lens on Human Nature Dr. Montessori approached children and human development as a scientist. Through her observations, she recognized that humans possess innate, universal characteristics and follow predictable patterns of development. At our core, we are a species designed to learn, to adapt, and to grow. By observing children through the lens of human development, Dr. Montessori identified specific stages of growth, which we now call the Planes of Development, and a set of Human Tendencies that drive learning and adaptation from birth to maturity. These tendencies are not random. They are evolutionary forces that guide humans to meet their needs and fulfill their potential. Education That Aligns With Nature Montessori education is structured around supporting these stages and tendencies. Instead of imposing learning, we respect and reinforce the natural unfolding of each child’s abilities. Montessori learning environments are carefully prepared to meet developmental needs, and the adult’s role shifts from teacher to someone who serves as an aide to life. This means adults serve as guides who observe, prepare, and support rather than direct. A Cosmic Perspective Montessori’s vision of human development goes beyond the individual. She saw human beings as part of a cosmic web of interrelationships. In this interconnected system, each part plays a role in maintaining balance and harmony. Humans have a special place in this system, not only because of our capacity to adapt but because of our consciousness of that very role. With this perspective, we recognize that education must also cultivate humility, wonder, and stewardship —qualities that enable us to live responsibly within this complex, interdependent world. In this context, education is not just about achieving success; it’s about supporting the growth of mature, adaptive, and aware human beings. The Power of Adaptation Humans are uniquely capable of adapting to a vast range of environments and social conditions. We have been able to move beyond survival and, in the process, have become creative, intelligent, and intentional in our adaptation. From birth, children adapt and evolve through interaction with their surroundings. Through their senses, hands, minds, and relationships, children construct themselves and their understanding of the world. Dr. Montessori identified key characteristics that support this adaptation. Humans have a long childhood, noteworthy for the development of our hands, intelligence, imagination, and social interdependence. These capacities are guided by the Human Tendencies, which not only move development forward but also shape who we become. The Human Tendencies These universal tendencies include the drive to: Orient to the environment Explore the unknown Order and make sense of the world Abstract and think symbolically Imagine possibilities Calculate and reason Work to shape and adapt the environment Repeat and strive for precision Perfect oneself through effort Communicate and associate with others These tendencies are innate, universal, lifelong, and evolutionary in nature. They cannot be eliminated, but they can be supported—or thwarted. When blocked, children will still try to meet their needs, often in less productive or more disruptive ways. Observation and the Role of Adults To truly support a child’s development, we observe with care to determine if children’s tendencies are being honored or obstructed. As Montessori-trained guides, we strive to look beneath behavior and recognize what drives it. This observational practice shifts our understanding of children and deepens our respect for their developmental process. Dr. Montessori’s work challenges traditional views of education. Instead of seeing adults as the agents of growth, Dr. Montessori emphasized that children are self-constructing beings. Education should not be about imposing knowledge but about intentionally supporting the natural process of development. Education as an Aid to Life Ultimately, we believe that education should serve as a vital component of life itself. When we align learning environments with the science of human development, supporting children’s creative process of adaptation, we open the door to profound potential. Montessori education offers not only a method but a visionary framework rooted in observation, science, and deep reverence for what it means to be human. It calls us to see children not as empty vessels, but as beings full of possibility, ready to become mature, capable, and compassionate citizens of the world. We invite you to visit our school to see how Montessori environments support the potential of our young people!

Imagine the scene. A young child is trying to get comfortable for a car ride, but nothing seems right. Parents (and maybe even siblings) try to help. However, with each suggestion, the child becomes increasingly upset and overwhelmed. When we see that our children are getting frustrated, often our immediate response is to offer help, usually in the form of advice: “Try this.” “Do that.” “Just calm down.” While our intentions are good, our children’s responses tend not to be positive. Depending upon the situation, they may get more overwhelmed, respond with resistance, or even shut down. Advice, even when helpful, isn’t always what’s needed in the moment. What often works better (with children and even adults!) is a different kind of support, one that builds connection and trust, rather than pressure. The Power of Curiosity Questions In the Positive Discipline approach, this alternative is known as curiosity questions. Rather than imposing solutions (think of this as “you should” kind of advice), these questions are designed to invite children into the problem-solving process. Curiosity questions shift the dynamic from a command-and-control approach to one of collaboration. Here are a few examples of curiosity questions: “What’s happening?” “What would you like to have happen?” “How can I help?” By asking instead of telling, we can give our children space to think, feel, and take ownership. Their brains remain engaged in a calm, reflective state rather than flipping into fight-or-flight mode. Even more importantly, children start to feel capable because their ideas and feelings are valued. Why This Matters Moments of frustration or challenge are inevitable. Whether it’s struggling with a seatbelt, navigating friendship dynamics, or facing academic pressures, children need tools to navigate those moments, and we need ways to guide without overwhelming them. Curiosity questions do more than solve the problem at hand. They: Build emotional resilience Strengthen communication skills Cultivate problem-solving and independence Foster mutual respect When we ask questions instead of rushing in with answers, we step out of the pressure to “fix” everything. We create connection instead of conflict. A Simple Shift Imagine a different response on that car ride. Instead of “You should move your backpack,” or “Just unbuckle and redo the seatbelt,” or “Take a deep breath and calm down,” what if the question had been, “What’s bothering you back there?” or “What would make things more comfortable?” The child may still have felt upset, but they would have been invited into the solution. Key Principles Using curiosity questions effectively, our tone, timing, and intent are critical. Keeping these core principles in mind will help immensely! Be Genuinely Interested When we ask questions, we want to make sure we don’t have a hidden agenda. Children are incredibly perceptive and can sense when a question is loaded or when it's a subtle way of getting them to do what we want. Curiosity questions are most powerful when they come from a place of authentic wonder and care. Ask because you want to understand their experience, not because you're trying to control it. Create a Calm First When children are in the middle of a meltdown, they aren’t able to process language-based information. If they (or we) are emotionally flooded, focus on calming and connection first. “I can see this is really frustrating. Let’s take a breath. We can talk about it when we’re both ready.” The focus, thus, is first on everyone feeling regulated. Avoid Accusatory Language Children are also incredibly sensitive to undertones of blame. Even well-meant questions can come across as judgmental if they're delivered with irritation, sarcasm, or disbelief. Focus on gathering information with empathy and openness. We want to avoid “Why did you…?” if it feels like an interrogation. Thus, it’s best to frame questions to understand. Listen Actively When a child answers a curiosity question, they’re offering a glimpse into their inner world. Pause. Make eye contact. Tune in with your full attention. Reflect back what you hear. Ask follow-up questions to deepen understanding. Active listening builds trust and strengthens the relationship. A good go-to question is, “Tell me more about that.” Be Patient Children—especially younger ones—often need time to process both the question and their thoughts. Thus, we want to avoid jumping in with another question or suggestion too quickly. Silence can be a powerful part of the process, giving our children time to think and respond. For the Road Ahead Curiosity questions are a cornerstone of respectful, connection-based parenting. We’ll face plenty of moments when instinct tells us to jump in and take control. However, sometimes the most empowering thing we can do is to slow down and get curious. With just a few simple questions, we can help our children feel calm, capable, and connected. In the process, we can also remind ourselves that guidance doesn’t always mean having all the answers. To learn about more examples of effective and respectful guidance, schedule a time to visit our school!

One of the many beautiful and empowering aspects of Montessori education is how it helps children understand themselves as valued members of a community. A key way this happens is through Care of the Environment, a form of Practical Life work that provides children with the opportunity to tend to the spaces they live in each day. By participating in this care, children begin to feel at home in their classroom, school, and community. They feel a sense of ownership and take pride in their surroundings, and in the process, develop a deep sense of responsibility and connection. The Outdoor Environment When considering the children’s environment, we're not just referring to indoor spaces. In Montessori, the outdoor environment is not an afterthought. Instead, we consider the outdoors to be a natural and essential extension of the prepared indoor space. For young children, who are absorbing everything from the world around them, the time spent outdoors supports development in profound and lasting ways. For older children and adolescents, outdoor spaces can be a place for self-regulation and deep focus. Now more than ever, when children tend to spend increasing amounts of time indoors, reconnecting with natural spaces is vital for physical, emotional, and cognitive health. Why Being Outdoors Matters Research, including the work of Richard Louv in The Last Child in the Woods, highlights a growing body of evidence that time spent in nature is critical to the healthy development of both children and adults. In Montessori, we recognize that outdoor time is not a break from learning. Rather, the natural world is a powerful space for movement, language, social development, and sensory integration. Time outdoors is learning time. Young children are in the midst of sensitive periods for order, language, movement, and sensory refinement. These windows of opportunity allow for an intense connection with nature that nourishes the whole child. Plus, the natural world’s beauty, order, and rhythm speak to our deepest human tendencies: to explore, understand, and belong. The Adults’ Role Outside Outdoor spaces become a rich environment for observation, guidance, and connection. Children are often more socially expressive outdoors, making this a critical time for observing group dynamics and supporting social-emotional growth. It’s also a time to model joyful, playful behavior. Children need to see that being human includes lightness and laughter, and outdoor time offers the perfect opportunity for us to play alongside children while still maintaining an appropriate level of guidance. We can also help children understand that different environments call for different behaviors. What is appropriate outdoors differs from what is expected indoors. As children gain different experiences, they come to understand how to conduct themselves with grace and courtesy on a woodland trail and a garden bed, or how to navigate the intricacies of fort building and group game dynamics. Montessori children learn to move through different scenes and scenarios with increasing awareness, sensitivity, and confidence. Setting Up Outdoor Spaces We want our outdoor spaces to feel like a true extension of our classrooms, not a break from them. As such, we are intentional about how the outdoor spaces are developmentally appropriate, deepen children’s understanding of cause and effect, and nurture a sense of order. We want activities in the outdoor space to have a purposeful intent so they support the integration of children’s will, intellect, and coordinated movement. At home, outdoor activities can provide open-ended play opportunities that encourage exploration and independence, as well as ways to involve children in purposeful projects. Here are some ideas to get started! Practical Life Provide tools for cleaning tasks: sweeping paths, washing outdoor furniture, scrubbing flower pots, washing the car, and wiping off outdoor toys. Encourage gardening: planting seeds, watering, weeding, harvesting herbs or vegetables. Offer animal care opportunities: refilling bird feeders, walking the dog, playing fetch. Sensorial Exploration Include sensory gardens with fragrant herbs, soft leaves, and vibrant flowers—like lavender, mint, and lamb’s ear—that invite children to touch, smell, and observe. Create a collection space for sticks, stones, pinecones, shells, and seed pods. Gross Motor Development Find natural structures like logs or balance beams for climbing. Encourage running, rolling, or playing games in grassy areas. Create sand or dirt pits for digging and building. Observation and Nature Study Set up bird feeders, weather tools, and insect hotels. Create small areas for quiet observation with a bench, blanket, or hammock. Add sensory elements like wind chimes or water features to create a calming atmosphere. Curricular Connections Math: count petals, measure plant growth, sort leaves by size and shape. Science: Tools like magnifying glasses and microscopes help them explore soil, insects, and plant life up close. Composting systems, rainwater collection, or native plantings foster environmental stewardship. Art: Natural materials become mediums for creativity, such as twigs for weaving, leaves for prints, and landscapes for sketching. Language: Storytelling, reading under a tree, or labeling plants and garden tools strengthens vocabulary and communication while keeping learning grounded in the real world. Observe and Adapt As with all prepared environments, the key is observation. What captures our children’s curiosity? Where are they returning again and again? What challenges are they facing? By observing carefully, we can adjust to our children’s needs and interests. A prepared environment supports the whole child and helps them feel connected, not just to the earth, but to themselves and their community. We’d love to share our outdoor spaces with you. Schedule a tour today!

August 31 marks the birthday of Dr. Maria Montessori. Thus, we want to take time to honor the roots of this movement, the visionary contributions of Dr. Montessori herself, and our shared responsibility to carry her legacy forward. At the heart of Montessori education is a deep respect for human potential. Unlike traditional models that begin with the adult's idea of what a child should learn, the Montessori approach emerged from deep observation and genuine curiosity. Dr. Montessori did not set out to create a new educational system. Rather, she observed children with scientific curiosity and developed an approach in response to their needs. It’s important to remember that Dr. Montessori was first and foremost a scientist. She was one of the first female physicians in Italy, graduating in 1896 with a specialization in pediatrics and psychiatry. In her medical practice, she encountered children who were often seen as uneducable. However, rather than accept this assumption, Dr. Montessori looked closer. A Discovery That Changed Everything In 1900, Dr. Montessori was appointed director of a university program for children with developmental delays. Observing their sensory-seeking behaviors in bleak institutional settings, she began studying how sensory experiences affect cognitive development. She designed hands-on materials and engaged the children in purposeful activity. The results were stunning: children who had been dismissed by society not only improved, but some went on to pass the same standardized exams given to their peers in traditional schools. Dr. Montessori’s response was not one of self-congratulation. Instead, she challenged the broader education system, asking: If children with significant delays could thrive when given the right environment and tools, why weren’t typically developing children doing better in school? This question launched a lifetime of work dedicated to understanding and supporting the natural development of all children. The Birth of the Montessori Method In 1907, Dr. Montessori opened her first classroom, the Casa dei Bambini, in the working-class neighborhood of San Lorenzo in Rome. Tasked with overseeing daycare for children too young for public school, she began by introducing simple, practical activities, starting with self-care and environmental care. She also provided an array of materials designed to engage children’s hands and minds. The transformation was extraordinary. Children who had previously been described as wild and unruly became calm, focused, and joyful. They took pride in their appearance and their surroundings. They concentrated for long stretches of time, developed social awareness, and, unprompted, began asking to learn how to read and write. Dr. Montessori was fascinated by what she called “spontaneous discipline” and the deep love of work she observed in the children. Through observation and experimentation, she continued to refine the materials, the environment, and the adult's role. Education Rooted in Development What emerged was a revolutionary approach: an educational philosophy based on the science of human development. Rather than seeing the adult as the source of knowledge and the child as an empty vessel, Dr. Montessori recognized that children come into the world with innate potential and a deep drive to learn. Montessori education supports this natural unfolding by honoring what Dr. Montessori called human tendencies, such as exploration, orientation, order, communication, work, and repetition, through carefully prepared environments that meet the specific needs of each developmental stage. The adult's role is not to instruct, but to guide, observe, prepare, and support. This vision of human development extends beyond the individual to a larger understanding of humans as part of a cosmic web of interrelationships. In this interconnected world, every part plays a role in maintaining balance and harmony. Humans have a unique place in this system, and our role requires conscious awareness, humility, and stewardship. In addition to fostering rich academic growth, Montessori education cultivates mature, adaptive, and compassionate individuals who are capable of making meaningful contributions to our interconnected world. The Enduring Impact of Montessori’s Vision Dr. Montessori eventually left her medical practice and professorship to fully devote her life to this work. She lectured around the world, trained teachers, wrote extensively, and advocated for children’s rights. She also always insisted that the focus remain on the children, not on her. Through decades of scientific observation, experimentation, and cross-cultural study, Dr. Montessori discovered that children, when provided with the right conditions at the right time, flourish. Her insights have stood the test of time. Today, there are approximately 15,000 Montessori schools worldwide, with over 3,000 located in the United States alone. For over a century, Montessori education has empowered children to reach their full potential—academically, socially, and emotionally. Yet Montessori is not just about individual success. It’s about building a better society. We know that children are not just preparing for the future. They are the future. By focusing on children’s holistic development, we are supporting a generation of individuals who are more connected to themselves, to one another, and to the planet. Carrying the Legacy Forward Dr. Montessori’s vision asks us to do more than remember her birthday. We need to believe in children, observe them closely, and prepare environments that honor their needs. This also means that we, as adults, approach our role with humility and a sense of curiosity. Our job is to accompany children as they create the future. In this way, Montessori education becomes not just a method, but a movement, one rooted in peace, interdependence, and the full development of the human being. Thank you for being part of this vision. Together, here at Crabapple Montessori we are carrying the Montessori legacy forward, not only by what we teach, but by how we believe in the children before us. Come visit to learn more!